- Babette Moeller

- http://www.edc.org/babette-moeller

- Principal Investigator, Math for All

- Math for All

- http://mathforall.cct.edc.org

- Education Development Center

- Marvin Cohen

- https://www.bankstreet.edu/directory/marvin-t-cohen/

- Senior Faculty Member

- Math for All

- http://mathforall.cct.edc.org

- Bank Street College of Education

- Barbara Dubitsky

- https://www.bankstreet.edu/directory/barbara-dubitsky/

- Senior Faculty Member

- Math for All

- http://mathforall.cct.edc.org

- Bank Street College of Education

- Teresa Duncan

- https://www.linkedin.com/in/teresagarciaduncan

- Expert Consultant

- Math for All

- http://mathforall.cct.edc.org

- ICF

- John Hitchcock

- http://ceep.indiana.edu/about/senior-leadership/john-hitchcock.html

- Director & Associate Professor

- Math for All

- http://mathforall.cct.edc.org

- Indiana University

- Nesta Marshall

- Instructor-Advisor

- Math for All

- http://mathforall.cct.edc.org

- Bank Street College of Education

- Matt McLeod

- http://ltd.edc.org/people/matt-mcleod

- Research Scientist

- Math for All

- http://mathforall.cct.edc.org

- Education Development Center

- Ellen Meier

- http://www.tc.columbia.edu/ctsc

- Director & Faculty Member

- Math for All

- http://mathforall.cct.edc.org

- Teachers College, Columbia University

- Hal Melnick

- Senior Faculty Member

- Math for All

- http://mathforall.cct.edc.org

- Bank Street College of Education

- Karen Rothschild

- Faculty

- Math for All

- http://mathforall.cct.edc.org

- Bank Street College of Education

Public Discussion

Continue the discussion of this presentation on the Multiplex. Go to Multiplex

Babette Moeller

Principal Investigator, Math for All

Math for All is a long-term effort to support teachers in making high-quality math instruction accessible to all students, including those with disabilities. For more than 15 years, Bank Street College of Education and the Education Development Center, Inc. have been collaborating to develop approaches for enhancing the preparation of pre-service and in-service teachers to help all students achieve standards-based learning outcomes in mathematics. Funding from the National Science Foundation has allowed us to develop, pilot-test, and formatively evaluate a multi-media professional development program that has been published by Corwin Press. Currently, we are working with researchers from ICF, Indiana University, and Teachers College, Columbia University, in partnership with Chicago Public Schools, to conduct a large-scale, randomized controlled trial (RCT), funded by the Institute of Education Sciences. The purpose of this study is to assess the efficacy of Math for All for positively affecting teacher and student outcomes. The results we are sharing in our video are from Year 1 of a two-year study.

We hope you will join us for an exchange about our work. Here are some ways in which you can participate:

- Share an anecdote about a child who learns math differently

- Share strategies (for learning math, for teaching math to diverse learners, for professional development, for research) that have worked for you

-Share your experiences as a Math for All participant or facilitator

-Send us your questions about teaching math to diverse learners and the Math for All professional development program and research

-Give us feedback about our work

Every day over the upcoming week, we will post one or two questions for discussion. Please check in frequently to contribute to the various discussion threads. We look forward to your contributions!

Matt McLeod

Research Scientist

Hello and welcome. Thank you for viewing our video. We have found some strong benefit to using open-ended tasks in our work. Please join our conversation by sharing comments about:

* Which open-ended tasks have you used in your classroom or school and what benefits did you see to using them?

* What obstacles did you have to plan around in order to implement these tasks?

* What strategies did you employ to ensure students' access to these tasks?

* What effects have your use of open ended tasks had on your students' mathematical identity?

Thank you so much. Looking forward to hearing from you!

Teresa Duncan

Expert Consultant

Hello everyone! Thanks for your interest in Math for All. Our study is designed as a randomized controlled trial (RCT), and meets the ESSA evidence requirements for Tier 4.

How are you determining which evidence tiers your professional development or school improvement strategies are at? What are some of the challenges you’re facing?

We'd love to hear your thoughts!

Sally Crissman

A worthwhile project indeed! Students who learn or approach math differently (or science in my case) make us better teachers:by doing the careful listening and learning to tailor a further challenge or an explanation to meet the individual's need, we have a broader repertoire are better prepared to meet the needs of all students! My own children were fortunate to have math teachers who valued a range of individual solutions to problems and made sure everyone in the class understood a classmate's strategy and rationale. And got to weigh the pros and cons of various solutions. Math was intellectually interesting for young learners. Glad you are doing this work!

Babette Moeller

Matt McLeod

Research Scientist

Thank you so much for your comments. It takes quite a bit of conversation sometimes to convince people this is not a curriculum but rather an approach to teaching and I agree that this approach could be easily translated to other subjects. Enjoy the rest of the showcase!

Babette Moeller

Principal Investigator, Math for All

Thank you for your comments, Sally! What has helped you as a teacher to engage in this careful listening and learning from your students?

Wendy Smith

Associate Director

Math For All looks like a great projects for teachers. Can you say a little more about the teachers who participate? Are these volunteers? Do regular education and special education teachers from the same school participate together? How long do teachers participate? Do you get any push-back that teachers don't have time to implement Math for All types of tasks or activities?

Babette Moeller

Hal Melnick

Senior Faculty Member

For the past 15 years we have worked in districts across the country. The five one-day-long monthly sessions have either been run by the developers of Math for All or we have studied two lead teachers in a school district running the five sessions. The facilitators from a district generally include one Special Ed leader and one General Ed lead teacher. The five sessions are all described in the Corwin package which includes a Facilitators Guide and a Participants guide as well as a DVD with all the Powerpoints and video cases embedded. And yes, the participants usual volunteer as teams of special ed teachers working with a general ed teacher . Each month they work as partners focusing their observations and planning of lessons with the same focal child in mind. Teachers generally have a month between the sessions to carry out their planned lessons and observations of the focal child, Watching a child learning is a very big part of Math for All. Then teams return the next month to share what worked or didn't work. We aim to build community where special ed and general ed teachers collaborate and grow in their instructional skills together. Push back is at times experienced but the shared benefits teachers feel from adaptations learned in the sessions serves as a productive payoff that seems to mitigate resistance. Teachers say they learn new ways to think about math content as well as adaptation strategies. They also tell us they get excited about learning and teaching math in creative ways by attending the five sessions each month and by viewing/ reading/experiencing the video cases.

Babette Moeller

Principal Investigator, Math for All

To build on Hal's response, we recruit teams of general and special education teachers who serve the same students to make their collaboration most meaningful. Teachers typically participate in the five PD sessions which are carried out over the course of one school year. However, the intend of our program is for teachers to continue their collaborative lesson planning long after their participation in the PD sessions. Ideally, we have all or most teachers from a given school participate; school-wide participation makes it so much more likely that the collaborative lesson planning will be sustained.

One way in which we are making the lesson planning process more manageable is by asking teachers to focus their planning on one focal student (a student who they have questions about). Teachers find this approach very helpful because the things they they plan to provide access to the mathematics for this student often helps many others in their classroom. Please see Marvin's post below for some specific examples.

Katherine Culp

There is such a deep and methodical body of research and expertise behind this project - it was ahead of its time years ago and it is so exciting to see it continue to move forward. Congratulations to the whole team on this project - Math For All only gets more impressive with time.

Babette Moeller

Babette Moeller

Principal Investigator, Math for All

Thank you, Katie!!! We've been fortunate to have had the support from NSF and IES and some private foundations to conduct extensive formative and summative research, which has allowed us to continually refine our program. For instance, most recently we have begun to develop tools and professional learning opportunities for school leaders, given the important roles these leaders play in sustaining and scaling up the collaborative lesson planning in their schools. As an another example, this past year we've worked with teachers around several "Problems of the Month", open-ended and multi-tiered math problems that have been developed by the Charles Dana Center at the University of Texas. We have found that these problems provide wonderful opportunities for teachers to provide their students with multiple entry points and pathways to engage in high-quality, rigorous mathematics.

boaz steed

Amazing work! The accessibility of a subject is crucial to the learning process, especially at such a young age. Im sure the kids and teachers working with Math For All will both benefit from the experience. It also is so important (and commendable!) to have such dedicated researchers and educators who are willing to expend their energy and time developing programs like this

Babette Moeller

Marvin Cohen

Senior Faculty Member

This project reminds us all, teachers and developers, that it is incredibly exciting when all children in our classes are able to be mathematicians. For this to happen we all, teachers, need to let ourselves also be mathematicians. It is so exciting!!

Marvin Cohen

Senior Faculty Member

Math for All has presented many challenges to us as developers, but more importantly to the teachers we have worked with. The process of working through these classroom challenges are where we see teachers working hard and succeeding. Teachers move beyond collecting and selecting lessons to thinking with colleagues about how to adapt and plan lessons for a focal child. They are deeply involved with a colleague in developing new instructional strategies using a neuro-developmental lens and a single focal child.

This planning for a focal child inevitably leads to new instructional strategies for the entire class. For many this often challenges their assumptions about how they make instructional decisions.

A simple example is when a teacher makes a check list for a child who has sequencing problems and has receptive language strengths. S/he planned the lesson with her MFA partner and they decide to make the check list available to the entire class. They reviewed student work samples and saw that several of the children had followed the check list. The strategy was shared with colleagues who also used it successfully.

The instructional decisions were made based on the neuro-developmental needs of a single focal child.

How do you make instructional decisions? Can you share a simple example with us?

It would be GREAT if a few of you could share how instructional decisions are made in your school and give an example of how an adaptation has lead to increased student learning.

Cecily Selling

This research is so important. I think that professional development that brings teachers together to talk about their craft, try new things, and reflect back on how things went is the most effective. Teachers in Japan have been doing it for years. I hope it catches on in this country.

Babette Moeller

Babette Moeller

Principal Investigator, Math for All

Thank you so much for your comments, Cecily! What do you think needs to happen for teacher collaboration and reflection around shared lessons to become more common in the U.S.?

Nesta Marshall

Instructor-Advisor

One of the potent aspects of the Math for All work has been the collaborative planning opportunities that grade-level special education and general education teachers have had to talk about their work with children in a safe space and with a supportive professional learning community. This was made possible by providing teachers with a neuro-developmental framework via which they could speak objectively, respectfully and constructively about how to refine, enhance and retool their instructional approaches in order to celebrate students' strengths while addressing their areas of struggle with strategies and tools that are aligned to their students' unique learning profiles. Worthy of commendation are principals who embrace the merits of these strategic planning and reflective opportunities by creating the time for teachers to engage in this collaborative discourse. Needless to say, principal buy-in is crucial. Albeit, teachers, too, need to be highly invested in the process as active participants who are learning and growing together in their role as educational practitioners.

Miriam Sherin

Professor, Associate Dean of Teacher Education

Such an interesting project and discussion! Your example of a teacher creating a resource for a target student that then becomes useful for others is an important finding I think. Along the same lines I'm wondering if you've found that encouraging teachers to focus on the learning of an individual student leads the teacher to pay more attention in general to individual students. In other words, when teachers are learning to teach in ways that are responsive to a student have you noticing if they come to apply that approach to students in the classroom overall?

Babette Moeller

Babette Moeller

Principal Investigator, Math for All

Thank you for your comments, Miriam! We've been finding that focusing on the learning of an individual student not only helps teachers to become more aware of individual students' strengths and needs in general, but it also motivates them to engage more deeply in the mathematics content. Finding alternative ways to provide access to math content makes it necessary for teachers to think about the math more conceptually. If you want to provide access to math to students who differ in their learning profiles, you cannot rely on teaching math procedurally.

Hal Melnick

Senior Faculty Member

Miriam, you ask a great question. Data is being collected ( both qualitative and quantitative) which may well give us more on this but anecdotally in some instances we believe there is transfer to all teaching and sort of a 'tuning in' on how diverse learners make meaning . I remember filming a lesson planning meeting in a school in NYC with special and general ed teachers and a math coach . It was so enlightening to hear Frances saying at the end summation discussion " You know Jordan hasn't changed. He's being more successful because we have changed ." She gave us all a lot to think about. What do you think she might mean by that?

Miriam Sherin

Professor, Associate Dean of Teacher Education

I wonder if Frances is recognizing that she has new ways to understand what students are doing and new tools for working with students? Great story!

Babette Moeller

Melissa Sheffer

This is a wonderful initiative, and I am so glad that you all have been able to continue to educate teachers about how they can better serve their students. I think Hal made a very important point, that when utilizing the strategies that Math for All teaches, the students aren't changing, but we as educators are changing. We can reach our students in a more meaningful way. I am just curious, over all the time Math for All has been around, about how many teachers do you think you have educated further on how to help students reach their math potential and a deeper conceptual understanding?

Babette Moeller

Marvin Cohen

Senior Faculty Member

I will get you that data on Wednesday. Thanks for your interest.

mtc

Babette Moeller

Principal Investigator, Math for All

Thanks for your comments, Melissa! We have had the opportunity to work with more than 650 teachers from 11 states over the past 15 years. These teacher reach about 13,000 students per year.

Are you in a teacher pre-service program, Melissa? How does your program prepare you for teaching math to diverse learners?

Nesta Marshall

Instructor-Advisor

A hearty welcome to one and all! Did the video pique your interest in learning more about differentiated instructional strategies for math tasks? How are you making math more accessible to diverse learners?

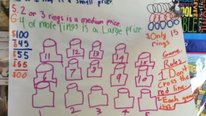

In our Math for All professional development training, we recently had the opportunity to watch teachers adapt the Measuring Up Problem of the Month Levels A and B math lesson (that is based on the story, Stone Soup) to support their students in ways that tapped into their students' neuro-developmental strengths and other aspects of their learning profiles. Here are some examples of how students with different abilities approached this math task in different ways. Some students figured out the solutions to the problem via a table with horizontally-aligned pictures that represented each ingredient (2 carrots, 3 green onions, 5 chunks of meat) and vertically-aligned numbers to represent the number of people for whom the soup will be made. Others used manipulatives such as colored tiles or colored post-its to figure out the ingredients needed to make soup for different numbers of people. (The tiles and post-its matched the color of the ingredients.) Some students placed the appropriate number of colored tiles in a pot to make the soup for different numbers of people. Other students drew circles on chart paper or in notebooks and then drew pictures of the ingredients inside the circles. (Each circle indicated one person's portion of each ingredient.) One student had plates that denoted a person; on each plate was placed square tiles that portrayed the person's portion of soup ingredients.

I'm eager for you to share examples of how you created opportunities for students to access math lessons/tasks using different approaches that utilized their affinities/interests, strengths and other aspects of their learning profile.

Barbara Dubitsky

Senior Faculty Member

A central theme of Math for All: demands of mathematical tasks. As teachers plan lessons we ask them to do the problem themselves and then to consider what they needed to do as they explored it. For example, the demands that were considered in a problem they were planning about three children in a heal-to-toe race with different shoe sizes anda different track lengths. Teachers noted these demands: reading the problem, remembering the directions, keeping track of the size of the shoes and track lengths associated with each child, talking to their partner, measuring and cutting shoes, staying focused, understanding what “each” refers to… You will notice that there were many demands that didn’t have to do with the “math.” As they became aware of the demands, teachers came to see their extended role in supporting children in math learning. They came to understand what got in the way for children – it was much more than remembering their multiplication facts. We find that simple adaptations go a long way: acting out the problem, using manipulatives, simplifying the wording of the problem, using see-through rulers, using sentence starters…

As we do this work with teachers they come to understand that math lessons have aspects that include: memory, motor skills, psycho-social skills, attention, language and of course others that are more like the ones that we usually associate with math: like higher order thinking, special ordering and sequential ordering.

We’re hoping to hear your examples of doing math activities hands-on when planning and adapting lessons for children.

Karen Rothschild

Faculty

Hello everyone,

We are so glad to see that many of you have taken an interest in our work. We are also interested in your work, and would love to engage in dialogue about it. One of the defining pieces of our project is intentionally bringing together both general ed and special ed teachers to plan lessons. We find that planning by looking through the lenses of both mathematics and learning needs helps us pay attention to how we can make adjustments to the structure of a lesson that maintains high level mathematics and yet makes it accessible to all children.

Have you had any experience collaborating on math with general and special ed teachers?

-how have you in your school been able to foster collaboration

-what benefits have you observed in co-planning and co-teaching

Wendy Martin

Excellent video Babette, and a great program! Taking a strengths-based approach to instruction is an excellent way to support all students, but especially those with special needs. We are using that approach on an ITEST project that supports students on the autism spectrum, and typical peers, who engage in maker activities. Math is definitely a subject that requires multiple strategies to make sense to diverse learners. What are some strategies that you or your teachers have come up with that have been particularly effective?

Babette Moeller

Karen Rothschild

Faculty

Hi Wendy,

Thanks for your comments. We ask teachers to do the tasks that they will assign and then analyze them through a neurodevelopmental lens. They consider what demands the tasks makes on memory, motor coordination, language processing, sequential and spatial ordering and more. There's a chart with all this in the video at 0:55. We then ask them to consider students and adjust the task in such a way that the mathematical rigor is maintained, but strengths of the students are leveraged and challenges bypassed as much as possible. How about you?

Babette Moeller

Principal Investigator, Math for All

Thank you for your comments, Wendy! And thank you for mentioning IDEAS--it is a great project. More information about it can be found here: http://cct.edc.org/projects/ideas-inventing-designing-and-engineering-autism-spectrum

The one general strategy that we have found to be most useful, is for teachers to engage in ongoing observation of individual students using a neurodevelopmental lens. It is so important for teachers to deeply understand what the strengths and needs of their students are so they can offer appropriate strategies for them to gain access to high quality math content. And while our work focuses on math, this strategy certainly works across all subject areas.

Jose Guzman

This is masterful work in terms of the development of good practice and powerful curricular experiences for all- not just for the students, which is key. In my own work with teachers, the richest explorations happen when we work through more open ended problems and focus on multiple entry points, when we work to monitor the type of tasks we are asking of our students, and when we are able to remove to some degree our own assumptions about a student's ability to process, which can only happen through thoughtful planning and a commitment to learn along side the student.

Babette Moeller

Karen Rothschild

Faculty

We totally agree that open-ended, high level problems with multiple entry points are the key to this work. We have been working in Chicago public schools where they have district wide Problems of the Month. Using those problems for our work has helped teachers collaborate across schools in the district

Bronwyn Taggart

From Barbara Dubitsky's comment above: "As we do this work with teachers they come to understand that math lessons have aspects that include: memory, motor skills, psycho-social skills, attention, language and of course others that are more like the ones that we usually associate with math: like higher order thinking, special ordering and sequential ordering."

For me, this is one of the most interesting points to come up in this project. I think neuro-typical people often assume that those of us who learn differently have just one, obvious challenge—e.g., a dyslexic is dealing "only" with decoding or reading comprehension. But like ripples in a pond, the effects of a processing problem can radiate out and influence many other areas of life.

Do you think the teaching strategies that educators learn to apply in this project could somehow be "reverse engineered" so that a student who learns to have success with math learning would be able to build on that experience of success to increase their confidence or help them in some other way than just academically?

Babette Moeller

John Hitchcock

Director & Associate Professor

Hi all – I’ve enjoyed reading the correspondence and have a new question. The Every Student Succeeds Act is now of course the law of the land. It shifts federal accountability to the states but still highlights the need for evidence-based practices. Hence, it seems there remains a need for randomized controlled trials and other forms of strong evaluation designs. So to my question: do others think that RCTs remain important? And do these designs by themselves generate the kind of evidence that we need to inform mathematics instruction?

Michelle Cerrone

Megan Silander

Given the dearth of research on the effectiveness of PD programs, it's hard not to see the value in conducting rigorous research such as RCTs that can estimate program impact. But there seems to be consensus in the field that we need to also be able to inform program design and implementation by going beyond an estimate of the average treatment effect and attending to variation in impacts and some of the mediators and moderators of the program's effect. We also need to examine impact and implementation over time, given how long we know it can take for a program to fully take root, and for instruction to change. I would love to hear about what you are learning regarding how schools and teachers differ in their PD approach, implementation/instruction (I'm curious to hear about how you're measuring differentiation!) and effects on student learning.

Michelle Cerrone

Babette Moeller

Ashley Lewis Presser

I agree that RCTs remain an important tool for understanding impact; however, they should be used after a program has had sufficient time to develop and benefit from several rounds of research. RCTs are one of many tools to develop evidence-based practices. One of my favorite articles is an Educational Researcher article from 2006 entitle "Feeling Better: A comparison of Medical Research and Education Research" (http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3102/001...). One of the things I love about this article, in addition to the direct comparison between fields, is the way it frames doctors as experts who facilitate and use research, whereas teachers are neither expected to engage in research nor really respected for their contributions to it neither of which is likely to help the goal of generating high quality evidence on practices that enhance learning. So yes, RCTS remain important and generate helpful knowledge, but we can also generate helpful knowledge using many different methodologies, and I'd add to the discussion the important role that teachers can and do play in educational research.

Michelle Cerrone

Babette Moeller

Michelle Cerrone

Great video and conversation!

I agree that RCTs remain relevant and are of value to estimating impact. Like many other things, not all RCTs are created equally and there are several factors researchers and consumers of research ought to consider when designing and determining the value of an RCT. As Ashley and Megan point out, the timing of the study is key. Ginsburg and Smith’s 2016 report does a nice job outlining threats to the usefulness of RCTs, along with recommendations in the context of What Works Clearinghouse (https://www.carnegiefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Do-randomized-controlled-trials-meet-the-gold-standard.pdf).

Babette Moeller

Barbara Dubitsky

Senior Faculty Member

Hi Bronwyn Taggart, concerting the question you asked:

“Do you think the teaching strategies that educators learn to apply in this project could somehow be "reverse engineered" so that a student who learns to have success with math learning would be able to build on that experience of success to increase their confidence or help them in some other way than just academically?”

We find that people who meet with success in mathematics, especially when they have had problems with it, may gain a sense of power. This feeling of power can permeate other aspects of their life. When teachers find successful adaptations for children when demands of mathematical tasks are getting in way they are more likely to succeed in those mathematical tasks.

Hal Melnick

Senior Faculty Member

What feelings are kicked up when you 'do' the math of the lesson?

Each Math for All PD session incorporates a video case study of a math lesson. In these video case lessons, we see children “doing” math. We hold the view that the way you learn math is by doing math, not just talking about the math. We have found if we expect teachers to really appreciate the multi- demands required of each task they themselves also have to do the math. At each session, before viewing the video tapes of children, teachers, in groups, are found using materials in deep conversation with each other working on the same task they will see children doing. Interesting conversations arise as groups of teachers unearth what they themselves know or are confused by. We hear some teachers admitting that they only learned rules or tricks (eg. they know the procedures) but have no clue about how operational concepts are connected to each other. For example they may not know that a ‘naked’ division problem can be better solved by some kids by thinking about it as a multiplication problem or maybe as a subtraction problem or even as a repeated addition problem. And we find, even though Common Core clearly affirms the use of models in math, too few teachers are well versed in how to help 8 / 9 year old students to visually represent multiplication using an open array model (and seldom do they know how that model lays a strong algebraic foundation for multiplying polynomials in middle school!! ). For the child with a strong visual spatial sense that may be their only ‘way in’ to understanding and remembering how to multiply 523 X 21. Some teachers share how hard it is for them to think flexibly in math since they have never been taught flexibly. Some even reveal their antipathy towards math ; sometimes referred to as math anxiety.

We have tried in each of the five sessions to help teachers play with big ideas in math and open up their minds to the multiple pathways one might explore any one math idea. Different learners can access big important math ideas as long as we find their ‘way in’. Often we find it's the same for teachers. Math for All provides access points for teachers as well as children. Teachers deserve to have that ‘ah hah’ experience they aim to provide their children. Math for All aims to provide some of that for teachers as needed.

How have you found to help teachers become facile , flexible, open thinkers about underlying math concepts? Have you ever encountered a teacher who has expressed their own fears or negative views about mathematics themselves? What supports work well?

John Hitchcock

Director & Associate Professor

Megan and Ashley, thanks for your input on RCTs and evidence. I fully agree that RCTs should be seen as one tool, albeit an important one. Others may have heard that RCTs are the "gold standard of research." I disagree. I do however think that these class of designs represent a gold standard in causal research (there might be a higher platinum standard) as long as it is understood that there are many important issues around implementation, acceptability, etc. that are best explored with other design-types. Ashley, involving teachers more is critical. I've spent some time worrying about the research-to-practice gap, but lately have become interested in the practice-to-research gap, wherein teacher innovations need to be understood by researchers. Megan, I suspect we're going to have some compelling evidence around mediators and moderators in the MFA study, but it will be hard to analyze these with standard statistical approaches given the power that is needed. But I personally hope we will be able to describe these issues using exploratory and qualitative methods since it is better to think of a portfolio of research rather than single studies.

Babette Moeller

Principal Investigator, Math for All

Our research shows that engaging teachers in sustained collaborative lesson planning holds great promise for enhancing the instructional and emotional support teachers provide when teaching mathematics, and students' engagement when learning mathematics. We have found that for teachers to engage in this ongoing lesson planning and professional learning, the engagement of and support from school leaders is essential.

We are interested to hear from school leaders:

** How do you support ongoing, professional collaboration and learning among your teachers?

** What supports have been helpful to you in having teachers work in this way?

We are also interested to hear from other projects that have utilized teacher collaboration as a strategy for improving practice:

** How are you involving school leaders in your work?

** What practices have you found promising for supporting ongoing, collaborative professional learning at the school level?

Thanks in advance for your input!

E. Meier

Following the discussion above regarding RCTs, the overall design for the Math for All (MFA) project also includes the collection of qualitative data to better understand the work from the perspective of the teachers and principals. We have interviewed them in both the control and experimental schools, giving us a better understanding of the overall context for the MFA work in the Chicago schools. By including qualitative data in this mixed RCT research design, we are able to include the voices of those most directly involved and affected by the project. What are your thoughts about mixed RCT designs? Should qualitative data have a role to play?

Marvin Cohen

Senior Faculty Member

I think that the range, the focus, and the quality of the research on this project has provided the PD team with invaluable ongoing feedback that has informed the work we have been doing.

John Ward

Sorry to be somewhat late to the discussion here, but if I understand it correctly your current PD model is to do meetings with teachers in day-long face-to-face sessions. Have you investigated the feasibility of conducting your sessions remotely? Is that a direction in which you would like to move, or are you seeing potential drawbacks in online delivery? This is quite the compelling project.

Babette Moeller

Babette Moeller

Principal Investigator, Math for All

Thanks for your question, John! We are very interested in looking into ways of conducting our PD remotely as we are trying to scale up Math for All to a larger number of sites. We are thinking of a number of possibilities, including partnering with local PD providers to prepare and support local facilitators, and conducting some or a portion of the PD sessions online.

Given the interactive and collaborative nature of our PD, it is challenging to imagine for it to be done entirely online. However, there are numerous combinations of face-to-face and remote/online PD options that we are eager to explore. For instance, in our current work with Chicago Public Schools, we have utilized a combination of face-to-face and virtual coaching to support teachers in their continued collaborative lesson planning. We have found that virtual coaching can work quite well in combination with face-to-face meetings and if there is local support to facilitate online video conferencing.

Have you participated in or conducted remote/online PD? If so, we would love to hear what your experiences have been.

John Parris

This is an excellent video explaining an important project. The depth of knowledge, experience, and wisdom of the Math For All team is unique. I've observed the project develop over the years and its commitment to reaching these students and the teachers who serve them is impressive and inspiring. My Congratulations on the work so far and may it continue to grow

Babette Moeller

Barbara Dubitsky

Senior Faculty Member

Thanks for your question, John. We have done some of our PD on line – we did a course for people who were learning to be MFA facilitators, totally on-line. We have also worked on line with teachers who need a catch up session because they had joined us late. We have thought a lot about how to conduct the PD on line. We would certainly want to do them live. We might have some hurdles to deal with -- creating a sense of community, needing to have many shorter sessions rather than the six-hour ones we have face-to-face, making sure there are a variety of manipulative and other materials at every site…

John Ward

Our project entails doing online PD. We are dealing with the same hurdles that you list. After our first set of pilot sections we started experimenting with a hybrid model, where groups meet face-to-face at least initially in order to meet one another, and we have tested some models where we do more frequent meetings. But we still want to enable PD in a completely online space, so we're always interested in ideas to facilitate more interaction among the participants, such as using social media for communication.

Babette Moeller

Principal Investigator, Math for All

Looking into the future, we are very interested in scaling up our program to widen its reach. Scaling up can happen at many different levels. It could mean spreading and deepening our intervention at the schools that we are already working with. It could also mean bringing it to a wider range of geographic locations and settings. We are interested in hearing from other programs to learn what strategies and practices you have found promising for scale-up.

And if you are part of a school district that is interested in enhancing its capacity to make high quality math instruction more accessible to diverse learners please let us know. We would love to partner with you!

Babette Moeller

Principal Investigator, Math for All

Thank you for watching our video and for contributing to the discussion! While the live discussion concludes today, we are eager to continue the conversation about Math for All and making mathematics accessible to all students. Please contact us directly with other questions, comments, or suggestions. You can also visit us at mathforall.cct.edc.org for more information, resources, and updates on our research.

Further posting is closed as the showcase has ended.